Joe Donchess: School dropout lived the "All-American" dream

Donchess, who grew up poor, benefited from a prep school scholarship and tutelage under Pitt's Jock Sutherland.

THE JOE DONCHESS STORY: A rags-to-riches tale of a grade school dropout who — by chance, fortune and hard work — overcomes seemingly insurmountable odds to achieve wealth and fame as an athlete, scholar and medical professional.

Coming soon to a theater near you!

Well, not really.

However, Donchess’ life has all the makings of a big-screen saga about the American Dream.

Donchess was born March 17, 1905, in Youngstown, Ohio, the son of poor Hungarian immigrants.

“I had lost my father when I was 11 years old and then had to quit school when I was 13 to help support the family,” Donchess recalled in a 1965 interview with the Chicago Tribune. “I went to work as an electrician’s apprentice — though I had to lie about my age — and finally went to work for General Electric.”

He missed out on a typical middle and high school experience until he met an unnamed figure.

This mysterious individual was described in articles as either a coach, an alumnus, a factory executive, a surgeon or something else.1 One thing’s for sure, though, and it’s that this person (or group of people) had been so impressed by Donchess’ earnestness and diligence that they either paid for his education or positioned him for a scholarship at Wyoming Seminary in Kingston, Luzerne County.

“I was a pretty good all-around athlete, playing on the company teams and some sandlot groups,” Donchess said. “Over a period of time, several of the G.E. engineers saw me and the potential and encouraged me to continue school.”

Sem had one of the country’s most prestigious prep school football teams and an established pipeline to major college football programs, including the University of Pittsburgh. Andy Salata, a Youngstown boy and friend of Donchess, had already been enrolled at Sem. Salata, who later played at Pitt, helped convince Donchess to take advantage of the opportunity.

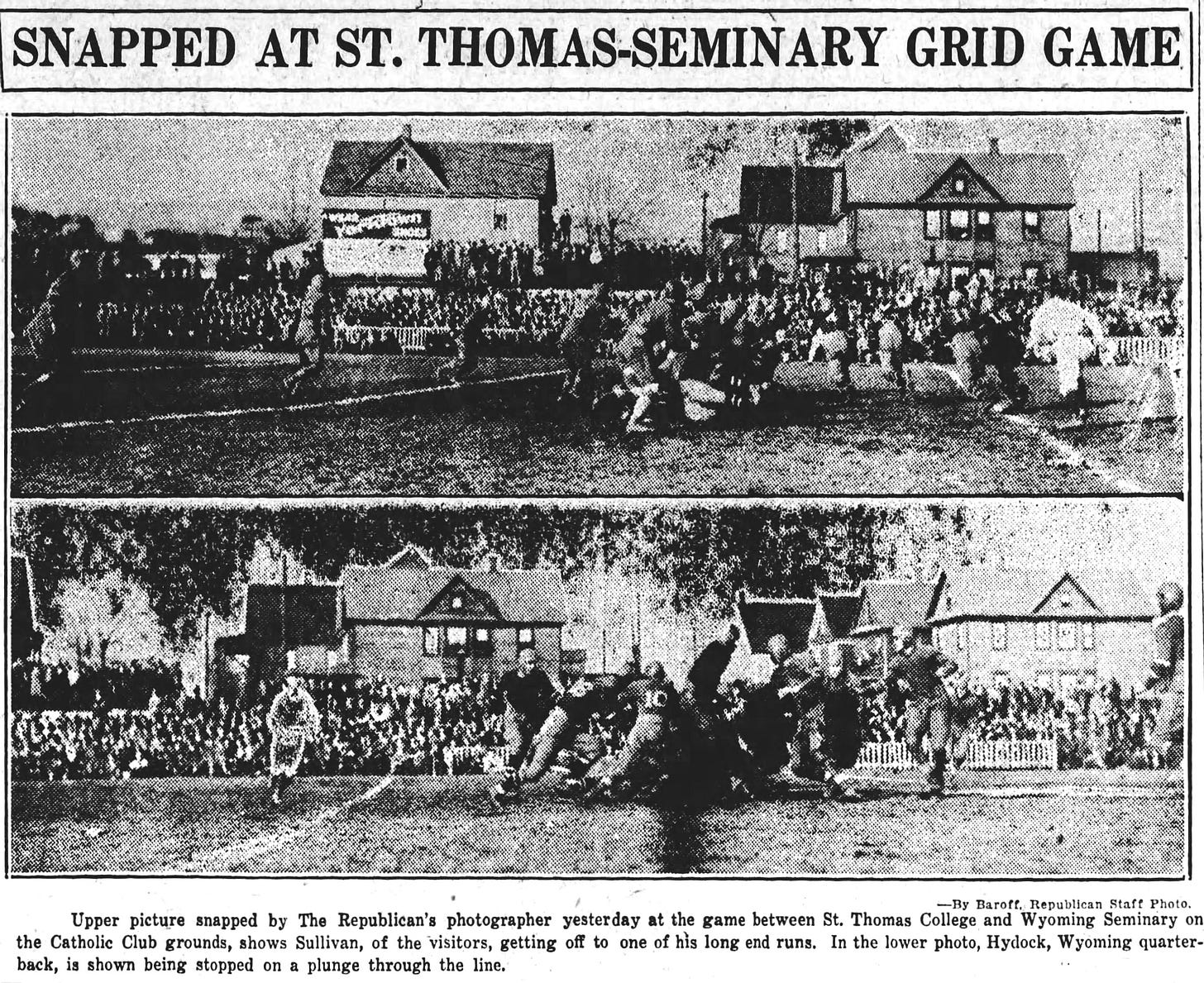

Donchess was a rare four-year varsity starter under Sem’s head football coach Ernest Quay. Donchess was the team captain as a junior in 1924. He also played baseball, basketball and was an honor roll student.

“When Donchess was here, he used to shovel coal into all the furnaces on campus,” former Wyoming Seminary President Jerry Packard said in a 2007 Times Leader article.

Following in the footsteps of Sem standouts-turned-All-Americans Ralph Chase and Bill Kern, Donchess also attended Pitt and starred at end for head coach Jock Sutherland.

As a freshman, Donchess made varsity and rode the bench. As a sophomore, he emerged as a key player and was Pitt’s starting left end in the Rose Bowl, a 7-6 loss against Stanford. As a junior, Donchess was selected an honorable mention All-American by the Associated Press, which selected Ohio State’s Wes Fesler for its first-team slot.

On Nov. 2, 1929, Donchess and Fesler went head-to-head to determine their supremacy. Donchess was a senior for Pitt (5-0) and Fesler was a junior for Ohio State (3-0-1).

“As youngsters, they lived within a few blocks of one another,” one report said. “Each had known the other but the acquistanceship was only that of small boys. They coasted down the same hills and splashed and dived in the same swimming holes.

“From grade school days, the paths of Donchess and Fesler took opposite directions. The former did his prepping at Wyoming (Seminary). Fesler became a star center and tackle at Youngstown South High.”

Pitt defended its home field and beat Ohio State, 18-2, in no small part because of Donchess.

“Fesler is great — make no mistake of that. He was Ohio’s defensive bet yesterday, making numerous tackles,” the Pittsburgh Press said. “But Donchess was greater and should have clinched unanimous All-America honors.”

By season’s end, Donchess and Fesler had each been selected consensus All-Americans by making multiple teams. Donchess did Fesler one better, though, and was a unanimous All-American.

As a team, Pitt went 9-1 (and 23-4-3 in Donchess’ three starting years). The Panthers’ only loss was again in the Rose Bowl, 47-14, against USC. Nonetheless, Pitt claimed a national championship from selector Parke H. Davis. The spring after Donchess’ senior season was marked by tragedy with the death of Leo Murphy, his Sem and Pitt teammate.

Donchess was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1979 alongside Heisman Trophy winners Howard “Hopalong” Cassady of Ohio State, Ernie Davis of Syracuse and Johnny Lattner of Notre Dame. Fesler had beaten Donchess to the punch and made the Hall in 1954. Fesler was also selected to the Eternal All-America Team, published in 1939 by famed sports writer Grantland Rice.

As a student, Donchess had originally been on the engineering track. He switched gears to medicine while at Pitt, however, and graduated from the university’s medical school in June 1932.

After his playing career ended, Donchess stayed with Pitt as the ends coach until graduating from medical school.

In 1934, Donchess was named the ends coach at Dartmouth under head coach Earl “Red” Blaik. Coaching at Dartmouth allowed Donchess to continue his medical training in pathology and surgery at Dartmouth Medical School and Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital.

There’s an alternative reality in which Donchess sticks with coaching football. After all, he learned from two of the greatest of all-time. Sutherland remains Pitt’s all-time wins leader. Blaik won three consecutive national championships (1944-46) at Army.

“Jock practiced until he had perfection. Every play, every block was set up to provide a touchdown,” Donchess said, contrasting the two. “Blaik had more of a military bearing. When he came near, the players would automatically snap to attention. Everyone had great respect for him.”

Donchess resigned from Dartmouth after the 1936 season and accepted the position of Assistant Surgeon in U.S. Steel’s Hospital in Gary, Indiana. He eventually became the Chief Surgeon, amassed a fortune and bequeathed millions of dollars to Wyoming Seminary, which has a boardroom and service award named in his honor. He also established Sem’s Quay-Adams award, named in honor of two of his school mentors.

Donchess retired in 1966 and died in 1977, survived by a widow, a brother and a sister.

Nearly 100 years after playing his final football game, Donchess stands as a testament to what a young person with talent and a desire to better themself can become with the help of sports.

The closest I’ve come to potentially pinning down this key figure is by way of a 1932 Pittsburgh Press article. The report says a Dr. Bunn — full name, I believe, Dr. Fred S. Bunn — from Youngstown City Hospital had taken a special interest in Donchess. Bunn, the hospital superintendent, died in November 1918 when Donchess was just 13, years before Donchess reached Wyoming Seminary.