Big Bill, Honest John and a timeless tale of humanity

Edwardsville's Bill Kern was at the heart of a 1938 college football controversy that swept the nation.

The “wrong down decision” was once the biggest story in American sports, a short-lived but career-defining saga whose ebbs and flows revealed the worst and best of human nature.

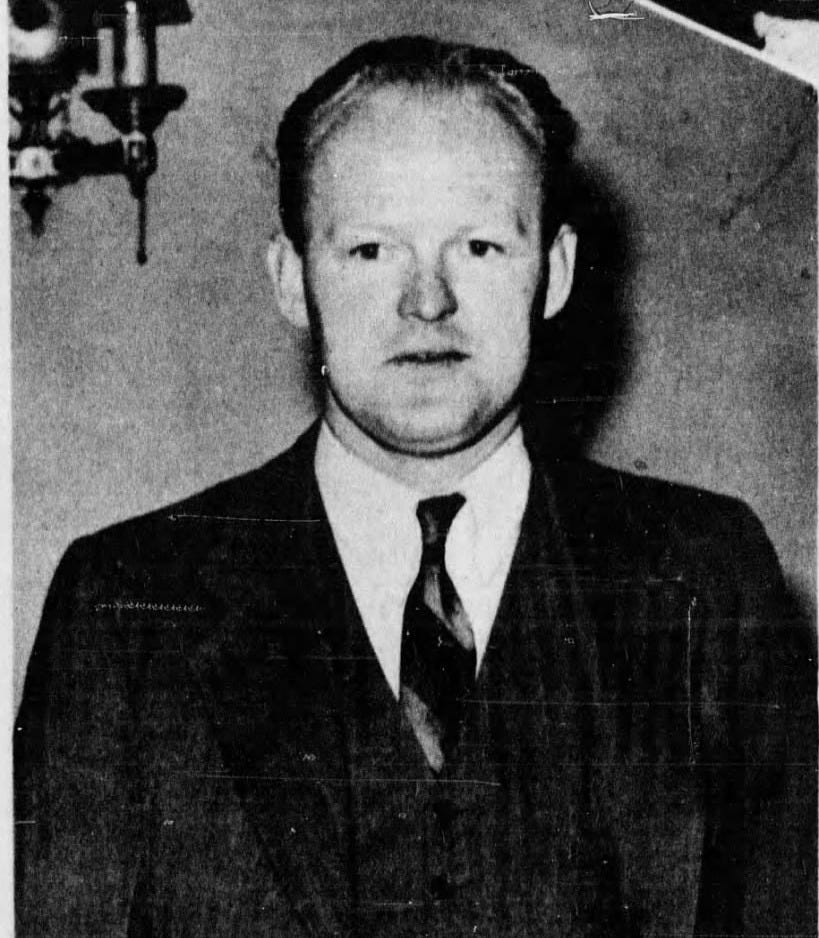

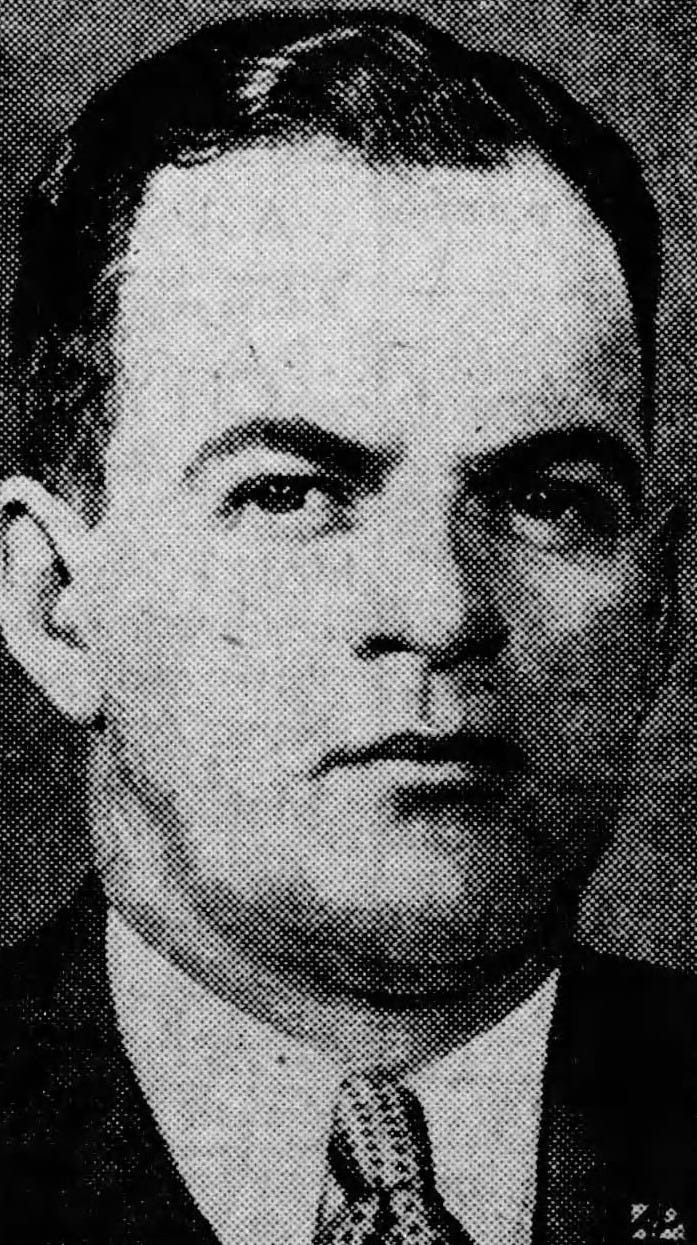

The conflict’s main characters were Carnegie Tech head football coach Bill Kern, 32, and referee John Getchell, 36, two wunderkinds in their professions.

Kern, who grew up on Zerby Street in Edwardsville and graduated from Wyoming Seminary, brought youth and Northeastern Pennsylvania to Carnegie. Kern was the youngest head coach of a ranked team and his assistant coaches included Eddie Baker, 29, of Nanticoke, and Joe “Muggsy” Skladany, 27, of Larksville.

Kern learned the game from its greats. He played for Jock Sutherland at Pitt and Curly Lambeau with the Green Bay Packers. His first assistant coaching job was under George McLaren at the University of Wyoming.

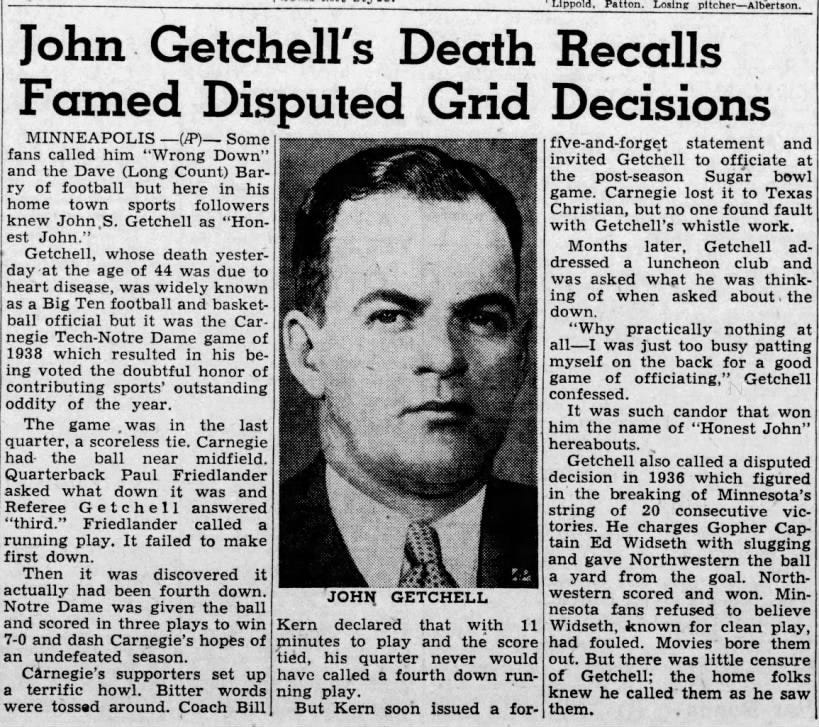

Getchell, a full-time stock and bond salesman in Minneapolis, Minnesota, was a seasoned Big Ten basketball and football official who refereed his first major contest at age 24.

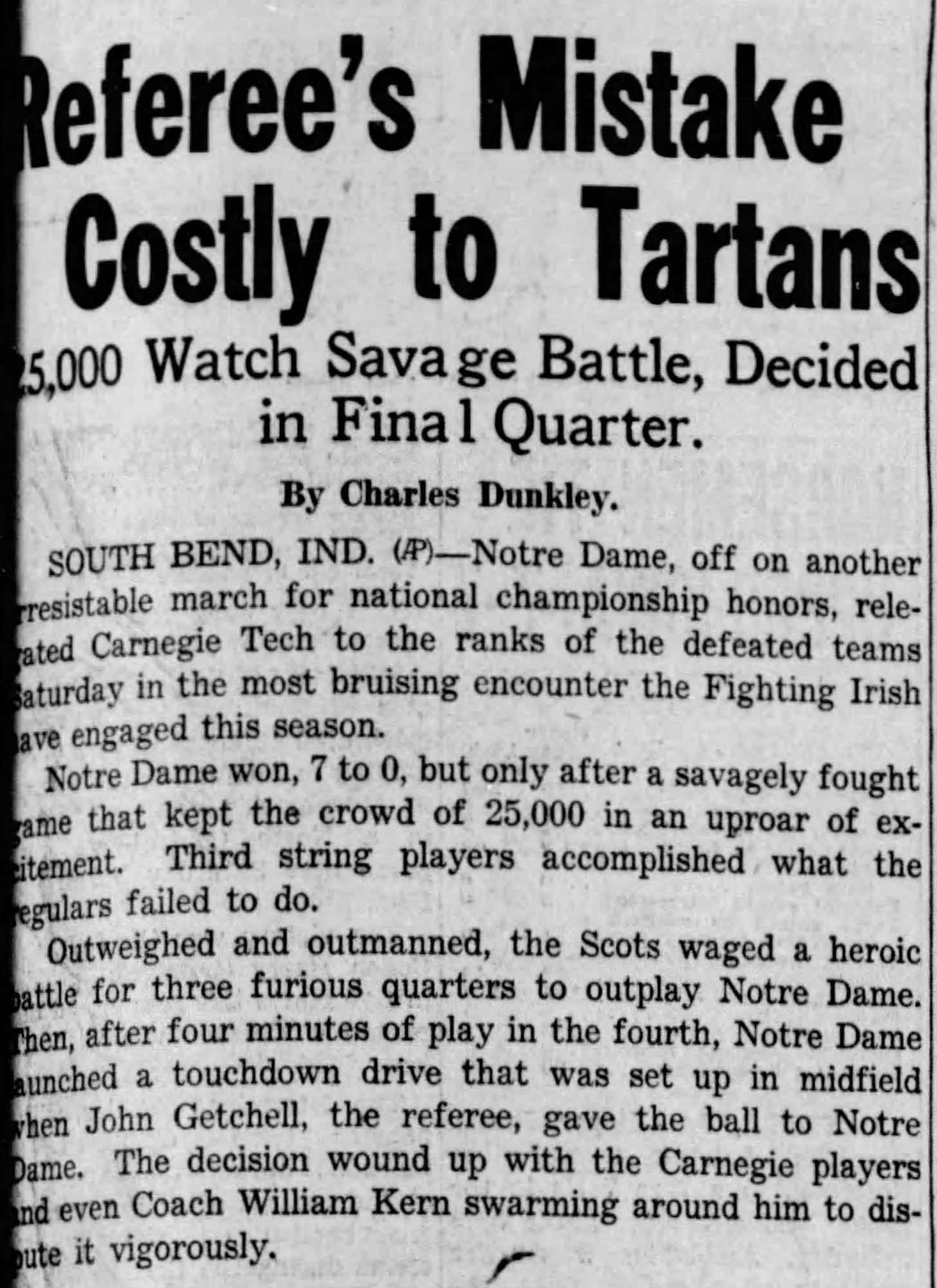

Kern and Getchell became permanently intertwined on Saturday, Oct. 22, 1938, in South Bend, Indiana. There, Kern’s bombasity turned to bullying and Getchell’s goof made him an overnight national pariah.

Carnegie Tech, a Pittsburgh engineering college now known as Carnegie Mellon, was 3-0. The upstart Tartans were ranked 13th — their first week ever in the Associated Press poll. Mighty Notre Dame was also 3-0, ranked fifth.

Kern, in his second season at Carnegie, had gone 2-5-1 as a rookie. Miraculously, one win was against Notre Dame. Despite Notre Dame’s staggering statistical edge in plays from scrimmage (61 to 31), yards (383 to 155) and first downs (15 to 2), Carnegie won on the scoreboard, 9-7.

“We’re on Notre Dame’s blacklist,” Kern told the AP before the 1938 rematch. “They’re gunning for us especially. This is one game they can’t afford to lose.”

Truthfully, neither team could afford to lose. Notre Dame and Carnegie each had legitimate paths to a national title and in five of the previous six seasons, the national title had gone to an undefeated team.

Good play and better luck catapulted Carnegie into the driver’s seat on this fateful Saturday. Notre Dame ran zero plays in the first half in Carnegie territory. Notre Dame fumbled seven times and lost four of them. Carnegie fumbled four times but held possession each time.

Despite this, the teams were deadlocked, 0-0, with 11 minutes left in the fourth quarter.

Then, all hell broke loose.

Carnegie had the ball at its own 48-yard line, 1 yard short of a first down.

Quarterback Paul Friedlander looked at the scoreboard, which stated it was fourth down. Having lost track of the downs, he turned to Getchell for confirmation.

“What down is it, Mr. Getchell?” Friedlander asked.

“Third down,” Getchell replied.

“But the board says it’s fourth down,” Friedlander said.

“I’m running this ball game, not the scoreboard,” snapped Getchell, who threatened Friedlander with a penalty if he continued pressing the issue.

If it had been fourth down, Carnegie would have punted. But, thinking it was third down, Friedlander called an audible. He handed the ball off to halfback Gerald White, who was taken down for a 2-yard loss.

Oh, no.

Getchell immediately recognized his mistake.

It was fourth down.

Getchell took the ball from Carnegie, signaled a turnover on downs and faced the wrath of Kern, who charged on to the field and demanded an explanation.

“Bill, I’m terribly sorry,” Getchell told him. “I made an awful mistake but there’s nothing I can do about it now.”

“You can uphold your ruling,” Kern replied.

“No, Bill, I can’t,” Getchell said. “Two wrongs don’t make a right.”

“You are the fellow who brought about the situation which deprived us of an opportunity to punt,” Kern said. “And you should do something about it.”

All the while, fans were confused about Carnegie’s decision to run the ball on fourth down and even more befuddled when this minutes-long exchange unfolded.

Eventually, Getchell dismissed Kern and the game resumed.

Notre Dame took advantage of the short field and traveled 46 yards over the next four plays, scoring a touchdown.

Notre Dame 7, Carnegie Tech 0. That score would be final.

Media coverage of the “wrong down decision,” as it became known, was extensive and sensational.

Among the outspoken masses was Kern, who fanned the flames and reportedly called it “the biggest bonehead” decision he’d ever seen by an official.

“The big crowd must have been too much for him,” Kern said in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “It’s a shame to have that happen on a team that’s pulling out like our boys were and were actually outplaying the strong Irish team. …

“We would have been right up there, even with a tie, with the famous Notre Dame team, and it’s tough to get knocked down when you don’t deserve it. I am speaking now, not for myself, but for the Carnegie boys who worked so hard to get ready for the game.”

Asa Bushnell, executive director of eastern intercollegiate athletics, said a fifth down should have been awarded to Carnegie.

“I never heard of an official making such a wrong decision,” Bushnell said. “But if any official ever calls the wrong down, I hope he will do the sensible thing and run the play again.”

Tom Thorp, described as “one of the oldest, wisest and most respected football officials in the country,” said Getchell should have given Carnegie another down or replayed the previous down.

“He had no right to penalize a team for a mistake of his own,” Thorp said of Getchell.

In the same article that quoted Thorp, an anonymous coach said he was surprised Kern didn’t take his team off the field in protest.

Notre Dame coach Elmer Layden acknowledged Getchell’s mistake but pointed out that Notre Dame was never given five downs, so Carnegie shouldn’t get an extra down either.

Layden said the public outcry was “unsportsmanlike,” adding that Getchell was a competent official who made a mistake and apologized for it.

“Tech feels that this incident cost the ball game,” Layden said. “But Tech had several scoring chances and we held them.”

Naturally, the discourse around Getchell’s blunder made it to the man himself.

Getchell on Sunday owned up to his mistake but said that both linesmen’s markers correctly showed fourth down. Critics responded that it was Getchell’s job to check with the linesmen and accurately announce the downs.

“It was just one of those freaks of football,” Getchell said. “It could probably happen anywhere, but probably won’t happen again in a million years.”

Getchell was told of Kern’s “bonehead” remarks and said it was “a little bit rough” to hear them.

Kern disputed some of his quotes, saying they were inaccurate. However, whether Kern blasted Getchell as harshly as reported or not, he felt obligated to defend his team, especially Friedlander. The quarterback’s call to run a play on fourth down was puzzling, without an explanation.

On Tuesday, Kern wired Getchell an apology.

“Reports of my comment on you personally very much exaggerated,” Kern said. “Consensus of our squad and myself that we forget the whole thing. We all wish you the best of luck.”

Kern publicly walked back his statements, too, saying he was “sore” and that he “said a lot of things (he) didn’t mean.”

The loss essentially ended Carnegie’s hopes of a national title. Now 3-1, Carnegie fell from No. 13 to 16. Despite winning, Notre Dame dropped from No. 5 to 7; but, still undefeated, the Irish kept alive their hopes of winning it all.

Fast-forward to the end of November: Notre Dame was 8-0, ranked No. 1. Carnegie Tech was 7-1, ranked No. 7.

Carnegie had the most impressive win of any team — a 27-13 upset of then-No. 1 Pitt on Nov. 5. A raucous celebration featured Carnegie students burning an effigy of Getchell on campus. The Pitt win, coupled with a victory over Notre Dame, would have almost certainly made Carnegie the favorite for a national title.

Instead, Carnegie settled for the Sugar Bowl against undefeated TCU.

However, before accepting the Sugar Bowl berth — the greatest achievement in Carnegie Tech football history — Kern had one condition. Getchell, he said, must officiate the game.

“I told Bill I thought it was a great idea, but I waited until I got home that night before going to work on it,” said Buddy Overend, Carnegie’s Athletic Director. “I put through a long-distance call to Getchell. I didn’t want anyone else to know what I was doing.

“When I was connected with Getchell and invited him to come to New Orleans, the man was so deeply moved that he almost cried. His wife told me later that he couldn’t believe it was true. He traced back the call to make certain he wasn’t being kidded some more about the unfortunate break at South Bend.”

In addition to the Sugar Bowl assignment, Getchell was invited to Carnegie’s end-of-year football banquet and Kern suggested that Getchell referee the next year’s Carnegie/Notre Dame game.

A columnist in the Shreveport Times described the newfound camaraderie between the former adversaries as a credit to Kern being “a regular guy” and “genuine sportsman.”

TCU won the Sugar Bowl, 15-7, and was crowned national champion by the AP. The Dickinson System rewarded Notre Dame with the national title, even after losing against USC to close the season.

Before the game, the Sugar Bowl crowd went wild when Getchell’s name was announced over the public address system.

After the game, Getchell, Kern and their wives dined out together and went for a night on the town in New Orleans.

“And not once,” reports said, “was that wrong down ‘incident’ mentioned!”

AP writers voted the “wrong down decision” as a runaway winner for 1938’s most freakish sports incident. Second place was the Cincinnati Reds’ John Vander Meer pitching two consecutive no-hitters.

The “wrong down decision” stuck to Kern and Getchell until the day they died. They did other things that were judged and remembered but never again did the 15 minutes of fame, or infamy, tick as loudly as they did in October 1938.

Neither man was perfect. Getchell crumbled under pressure. Kern lashed out. Both men made mistakes in a high-profile, high-pressure moment. Life’s too short for grudges, though, based on their actions in owning up to errors of ability and character, forgiving, forgetting and letting their high regard for each other manifest in their gestures.

Kern continued coaching through the 1940s and moved to a bigger program, West Virginia University. He never again reached the heights of 1938, however. He was the prestigious American Football Coaches Association Coach of the Year — an unheard-of honor for someone at a small school like Carnegie.

When Kern, 79, died in 1985, the “wrong down decision” occupied four paragraphs in his obituary in Pittsburgh newspapers. Kern’s gesture — asking that Getchell officiate the Sugar Bowl — was prominently mentioned.

Getchell’s hometown newspaper, the Star Tribune, wrote in May 1945 that Getchell was the most important official in the state and one of the best-known sports figures Minneapolis had contributed to U.S. sports.

Unfortunately, those words were written in memoriam.

Getchell had been in good health and just purchased a new home. He complained of an illness on a Sunday morning. He died of a heart attack the next day in the hospital. He was just 43, leaving behind a wife and two teenage daughters.

Getchell’s obituary was picked up on the wire and ran in newspapers across the nation, most of them not only mentioning the “wrong down decision” but writing it in the headline.

Getchell’s aforementioned Star Tribune obituary painted a layers-deep portrait of the man. Ever the sportsman, he was a reporter before becoming an official, a practical joker and someone with more friends than anyone else in Minnesota.

“He loved to live and he lived to the hilt,” the report said. “He was an asset to any gathering.”

The obituary also addressed the “wrong down decision” and commended Getchell for shouldering the blame and never dodging responsibility.

“No wonder,” it said, “they called him ‘Honest John.’”